alelanza wrote:Not so sure F1 engines would benefit from variable timing/lift

They would benefit, but the biggest benefit would be fuel saving during say a safetycar period where they can't go for full. This was also were Audis direct injected and later diesel Le Mans racers saw the biggest improvements. Of couse, even a small saving during the race can mean quite a lot.

WhiteBlue wrote:

I don't think that they had balance shafts. At least I cannot see that in the above picture and nothing is mentioned in the story of the engine told by Paul Rosche himself. The engine did 11.000 rpm in race trim and made 1000 bhp available. In qualifying for one lap they could activate almost 1400 bhp, but the upper con rod eye would have been stretched to one additional millimeter.

Their biggest problems were cooling of the pistons which they did by injecting castor oil into a cooling channel in the piston. The other problem was knocking. They had no control over the proper ignition until they used an old trick of WWII aircraft engines. They used methylbenzene C7H8 for fuel which is poisonous like hell but has supreme knock resistance.

If you build a similar engine today much of the material selection will be different like the engine block which was made from cast iron. Today they would probably use cast aluminum alloys.

The specification detail from gurneyflap show that the engine made the power from the turbo pressure and not from the rpm. They went from a 3 bar standard pressure to almost twice that with 5.5 bar. But the engine would do this only for one hot lap. So quali engine life was probably less than 20 km.

I would not know what the FiA will be going for with the new engine other than a certain power level and best fuel efficiency. We know from Norbert Haug that target power will be 600 bhp. It means that the old BMW engine would be running well below 3 bar turbo pressure.

I believe that the emphasis could be on higher revs (higher revs make for better efficiency) like 13.000-16.000 depending of the harmonics of such an engine type. I know very little about the harmonics so someone who has experience in race engins should say something.

I would find it totally impossible to run with special fuel again as they did in the eighties. We would most likely see standard grade petrol with 5-10% bio fuel added.

My assumption is that the peak power will be limited and that the development race will be for the best fuel efficiency in partial load conditions. The team which runs the leanest engine under partial load will have to carry the least fuel and will have to detune the engine latest.

So variable valve timing for avoiding pumping losses, exhaust gas recycling, stratified direct fuel injection, ion current measuring and all the modern technologies for increasing the combustion efficiency should all be employed.

The BMW engine produced at the most 900 hp in race trim, as the figures you post will tell you. This was roughly 100 hp down on what the most successful F1 engine of the late eighties, the Honda, produced.

That the engine produced more than 1300 hp (which in some myths have become both 1400 and 1500 hp) was based on an estimation of a flash boost pressure reading on Monza in 1986. It's also worth to note that this engine didn't last the whole qualification lap, which was run without a wastegate. Engine failures were also quite common with the BMW engine.

In 1987 a boost restriction of 4 bar absolute was introduced which limited the use of the qualification engines.

Methylbenzene, or toluene is about as toxic as gasoline in general, unlike regular benzene it is for instance not a cancirogen. I do however believe there were some other stuff than toluene in the fuel BMW used. You can check the thread below regarding the BMW fuel supplied by Wintershall.

http://forums.autosport-atlas.com/index ... opic=34397

Honda used a 84% toluene 16% n-heptane mix, but this was during the later years when fuel restrictions were introduced. First 240 liters in 1984, then 220 l in 1985, 195 l in 1986 and finally 150 liters in 1988.

The fuel used also had to meet the specification of regular pump petrol of the time. There was also a maximum research octane number of 102, and of course oxygenates like methanol wasn't allowed, which otherwise would have made a very good fuel.

The BMW engine had no balance shafts and the pistons were oil spray cooled using engine oil, not castor oil. The piston did have a channel inside it for oil cooling, much like current production diesels, and like many WRC and Le Mans racing engines have.

Later designs such as the Honda RA165E used a nodular iron block which is probably a better choice for a high boost engine than both aluminum and grey iron. Nodular iron is much stronger and more ductile than grey iron which means thin wall castings can be used, and it's fatigue properties are much better than aluminum.

In 1988 Honda RA168E produced 680 hp at 12,500 rpm, and 620 hp in fuel save mode consuming 272 g/kWh (equals an efficiency of around 32%). The boost pressure was 2.5 bar absolute.

As frictional losses increase significantly at high speed, you want to keep the speeds down for the lowest fuel consumption.

xpensive wrote:A rather heavy contraption really, 170 kg för a 1.5 I4, wonder what the reasoning for sticking with the stock cast-iron block was?

Marketing perhaps?

Cost I suspect. Infact, BMW had been using this engine in several racing series before F1, both in naturally aspiranted form and turbocharged. So based on that, BMW's Motorsport department figured that this engine could be turned into a competive F1 engine for a rather moderate cost. Essentially the same concept as the 'FIA standard engine' 30 years ahead of its time.

Later purpose designed engines used other solutions. Honda and Ferrari did for instance use blocks of nodular iron, and compared to these the four cylinder BMW had a weight handicap of 40 kg. It was also around 100 hp down on power compared to the Honda in race trim.

marcush. wrote:the engine blocks were indeed greycast iron ,BMW standard engine blocks but fully machined and polished inside..

It is no myth that the oldest blocks give best hp and anyways grey car iron blocks are stored to settle in the backyard ,exposed to the elements.. I would not be surprised if Rosches boys were really urinating on the blocks waiting for machining back then..

you know bavarians drink a lot of beer ...and at these times it was surely normal to have a beer or two or three during working hours..i know a guy who worked in the engine preparation in munich during these years of turbo crazy ,maybe i just ask next time I bump into him..

It is a myth that they used old blocks. An engineer that worked for BMW at the time with this engine was recently asked about this, and after having wondered where the story came from, he did indeed confirm that this was not the case. He said that they tried an old block only once and that engine failed on the dyno.

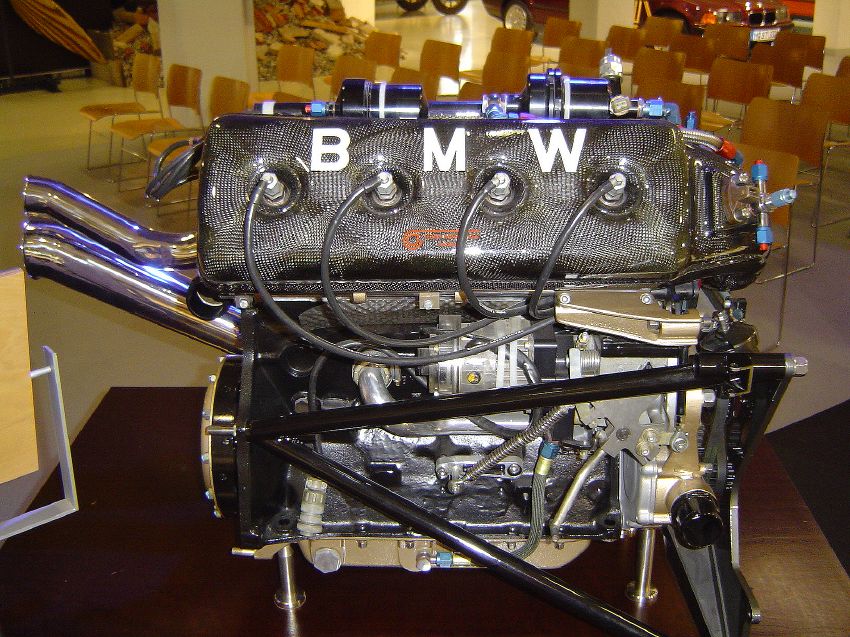

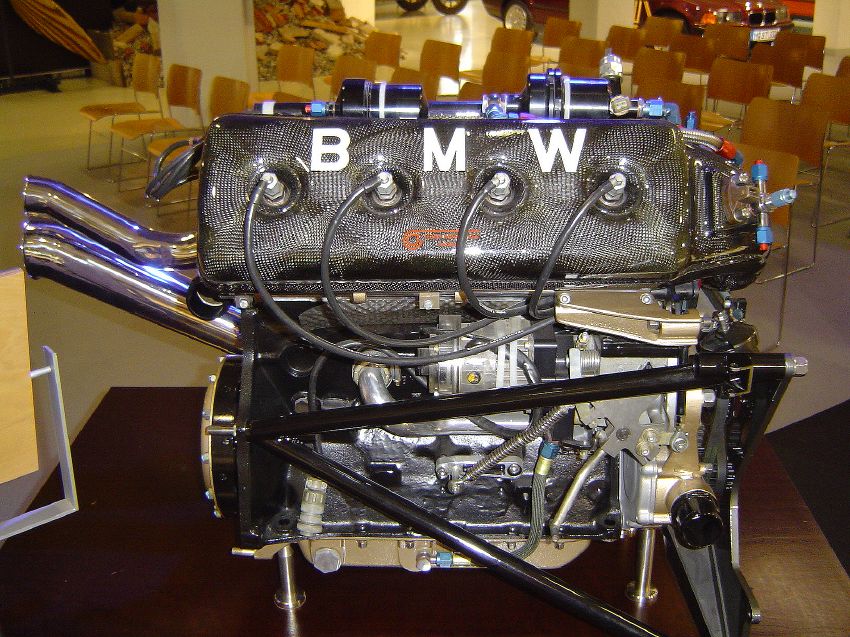

It is however possible that they did some sort of stress relief by heat treatment on the new blocks. I do know they machined the blocks to remove unneccesary material. You can see t if you look at the block on the picture below, the surface is a bit rougher where they have machined away material. Not exactly done with the best finish in mind. The regular oil return from the head is also missing, you can see the piece of it that is left a bit right and down from the cooling inlet passage. This cooling routing also differs from the stock engine

xpensive wrote:agip wrote:Do you think just 1 bar of boost will be allowed?

I have no idea, but I needed some even number input data to get a power-figure down.

If a 2.4 produces 760 Hp at 18000 rpm, then a 1.5 should proportionally mean 320 Hp at 12 000 Rpm.

Add a 1 Bar boost and you are at 640 Hp, 2 Bar and you get 960 Hp.

With fuel restrictions engine speeds will be lower. It will also be easier to use direct injection and other technologies at lower speeds.

xpensive wrote:I did not pick 12000 rpm arbitrarily, the BMW I4T of the 80s stopped at 11500 even without an FIA rev-limitation,

why I think it has something to do with the increasaed fuel burning-time of a turbo?

Besides, I guess the higher loads itself puts a natural limitation on speed.

Anyone?

The engine was unable to handle higher speeds. The blocks cracked or something like that. The reason was mechanical anyway.

alelanza wrote:

Hmmm... i definitely have no clue what you're talking about, do you have a link to the source you got this idea from? that may help me.

You can't avoid the throttle, whether you use a plate or valve lift and timing to throttle an engine, you still need to throttle it, otherwise the partial load term wouldn't even exist, you'd be at WOT all the time. Saying you get full gas flow through the engine makes it sound as if you have some magically produced mass flow and that the only thing standing in line between intake and exhaust is the throttle plate, but there's more things, ie the engine itself which after all is the one producing the flow, so i don't see how getting rid of the throttle plate would give you 'full gas flow through the engine'. Care to explain or link?

For other readers. This also makes me think about the vacuum a race engine produces, perhaps someone with engine knowledge may be able to answer this. Given the aggressive cams/huge valve overlap of a racing engine, your vacuum signal is always extremely low, i can only imagine that on an 18k optimized setup it will be minimal. So with this in mind, would you gain anything by using valvetrain as a throttle device on an engine that spends most of its time at full throttle? could you really offset the increased mass and friction (which again BMW hasn't gotten to make sense past 6k rpms) on an F1 application?

You can rid of the throttle by two ways; use the Atkinson-Miller cycle with either early or late inlet valve closure and/or use stratified charge, possebly with external cooled EGR.

alelanza wrote:

In practice as well, BMW has been doing that for a while in production vehicles, it's the valvetronic stuff i referred to a few posts ago. I think other manufacturers do it as well, and i also believe it does not work in all part throttle conditions, ie they still have a throttle plate for certain scenarios.

I agree with you that it's a good idea. But my question is, is it a good idea for F1? If a big (though perhaps not huge) manufacturer such as BMW hasn't gotten the technology to work in their street performance applications, how would F1 teams with much less $ and a much different focus get it to work?

We know the problem of partial throttle is pressure differential between both sides of the piston, thus i ask, on a racing engine with a much lower vacuum signal than that of a sub 6K rpm street and thus (I think) more efficient at partial throttle, would you truly gain anything?

BMW says their system stops being efficient past 6k due to the friction losses incurred by the larger valve train. Now i'm not sure if that info is up to date, the system has been in use since 2001 after all. But this makes me think, and please correct me if i'm wrong, that if you have less to gain due to less vacuum then on a racing engine this system would stop being efficient at much lower revs. Of course I'm pretty sure valvetronic is not the only solution out there, thus why I ask what kind of setup would make sense on an F1 engine.

Otherwise i feel it's another example of people asking for street car technology to be transferred to F1 just for the hell of it, losing sight of the profound differences between their grocery getter and what should be a firebreathing monster in 4 wheels set out to entertain us 19 times a year. In fact, when you get down to it 4 wheels are about the only thing they share in common hehe.

BMW's system is mechanical, but there are other ways to achieve the same thing. Recently we saw Fiat introducing a system using hydraulics to control valve lift and duration using the exhaust cam as an hydraulic pump. Another way is to use pneumatics, this has some advantages as the working fluid is clean in case there is a leak and it is not as temperature dependant as oil. In that case the valvetrain won't be heavier than the valve plus a small piston inside a stationary pneumatic cylinder. The movement of the valve is then measured for closed loop control using for instance laser.

madtown77 wrote:

*EDIT: Also, remember that even a fully open throttle is not lossless. Lot of turbulence at high air velocities on a throttle blade.

The pressure drop over an inlet valve very low. This is a simulated graph over whats happens during the intake stroke using GT-Suite. As you can see the cylinder pressure closely follows the inlet port pressure.

machin wrote:Just to clarify for other readers (as I didn't think it was clear from the post): What WB says is true for Diesel engines... where you can operate without a throttle and simply inject less fuel, but for a petrol engine injecting less fuel results in really high combustion temperatures and very short component lives... to remove the throttle plate from a petrol engine you have to re-introduce a throttle in another way (I think WB suggests using variable valve lift to achieve this), but this means that you don't get the effect he has described above.

Also, its worth bearing in mind that a turbo diesel engine sucks in far more air at full load (i.e higher injection quantities) than at low loads (low injection quantities) because the turbocharger will be working harder due to the higher exhaust temperatures (i.e. producing higher intake gas flow, and hence exhaust gas flow)... so even an unthrottled turbocharged diesel has a much higher exhaust gas flow at high load than at low load, so there's no easy solution to obtaining a constant exhaust flow for the diffuser....

Temperatures will peak at roughly lambda 1.1, if you go richer or leaner than that the temperatures will drop. Of course, going leaner than that with a gasoline engine is easier said than done. When going lean with a gasoline engine it will begin losing power and efficiency as the combustion duration increase. Then it will start misfiring, and then it won't fire at all as the mixture becomes too lean.

As I mentioned above you don't need to throttle a spark ignition engine, you do however need to maintain a burnable mixture in the cylinder by either a stratified charge or by reducing the amount of air the engine consume.

When you use early intake valve closure for instance you a re not introducing 'another throttle' as you claim, but what you're doing is in effect decreasing the intake stroke and as such there will be no throttling losses. In effect you're also decreasing the compression ratio in relation to the expansion ratio, so you will also gain engine efficiency in the thermal cycle too.

ringo wrote:Mass cannot be created nor destroyed, so it's logical a leaner mixture has less mass.

fuel density is much less than the air.

Mass flow is always mass fuel + mass air. The gas flow is dependent on it's energy whic is in turn dependent on the calorific value of the fuel.

The fuel affects the mass (since it's part of it) as well as the kinetic and thermal energy of the exhaust gas.

For any given power level, a lean mixture will result in a higher exhaust flow than a rich mixture.

To use all the oxygen in 1 kg of air we need 68 grams of gasoline thus the total exhaust mass will be 1068 grams. Now, if we burn the fuel at lambda 0.5 rather than lambda 1, we need to add 136 grams of gasoline instead of 68 grams, giving a total 1136 gram exhaust. If we go lean to lambda 1.5 instead we will still need the 68 grams gasoline to maintain the power level, then we need 1499 grams of air adding to a total exhaust mass of 1567 gram.