Aston Martin's engineers have found themselves with a somewhat schizophrenic single-seater

In the last fifteen months, they have signed up a lot of personnel, especially from Mercedes and Red Bull, and with very prominent figures. The practical key was not the big names like Dan Fallows, Eric Blandin or Luca Furbatto. They draw the outlines, they are the grey matter, but it's their acolytes, the engineers immediately below them, who execute the actions and bring the ideas to life.

Lawrence Stroll didn't exactly recruit a handful of these sergeants, but teams of them, working groups in specific areas. The guys who did the front end of the Mercedes that won eight consecutive titles started to do the same in the green team, or a small group from Red Bull started to take over other areas, such as the belly of the AMR23.

By the time all of these arrived, around the summer of 2022, the basic concept of the current car was well underway. To change everything and create something different would entail expense, time, and raise doubts in the face of tight deadlines. The logical thing - and this is pure speculation - is that all these people helped develop the current car, but they put most of their brainpower to work on the 2024 car. They helped, yes, but their real footprint will start to take shape next year.

What happened in practical terms?

It happened that the newcomers brought many solutions capable of repairing a car, but not of changing its basic concepts. The car changed its skin, but did not mutate to be a different car... and this is not new.

In 2020, the FIA World Council ruled that Renault's allegations against Racing Point, the predecessor of today's Aston Martin, were true. They were that the pink car, which looked like a Mercedes painted in a different colour, had copied certain parts related to its braking system. The penalty was $400,000 and 15 points deducted from the final standings. Racing Point admitted in court that one of its employees had 3D scanned the previous year's winning car. FIA said that apart from the sanctioned detail, on the outside it might look the same, but on the inside it was different.

The suspicion of several rival team engineers is that the pattern is replicated. The "Pink Mercedes" went into that season in a flurry, however with grafts developed in and for another car. Those solutions solved problems immediately, although they were very difficult to develop within a concept that was alien to them.

The result was a noisy start to the year, and a very diluted finish, and this is exactly what is happening in 2023. If the pink Mercedes surprised many in 2020, this season the one that many call "The Green Red Bull" stunned those who would end up chasing it.

From one year to the next, and with minimal changes in regulations, no one is stealing the wallet of those who have shared the victories for a decade. Aston Martin's early season lead was as true, real and enjoyable... as it was temporary. Mercedes left them behind, Ferrari also gave chase, and in McLaren's calculations -something they don't say publicly, but they do say internally-, things have to be very bad for them not to finish fourth, fifth to the green ones.

The mystery

When Dan Fallows, one of Adrian Newey's right-hand men, changed bosses, many thought the AMR23 would be an aerodynamically efficient car. The reality may be disappointing for those who came to that conclusion. The AMR23 fails in the fast corner, where it does not generate the desired downforce, and on the straights it is slow and where favourable aerodynamics could help.

The AMR23 has the typical behaviour of midfield cars: they tend to do well on a certain type of track, but not all of them; the really good cars do well under all circumstances, and the ones that close the qualifying table don't perform anywhere.

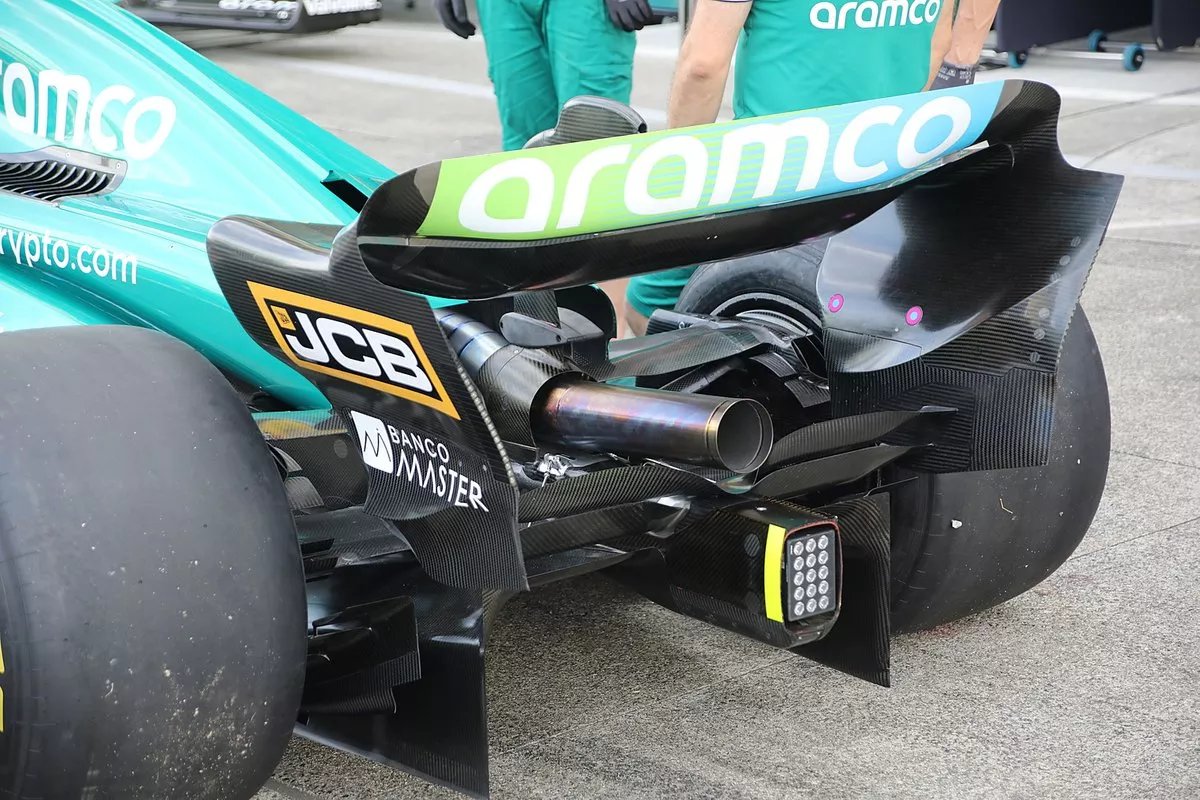

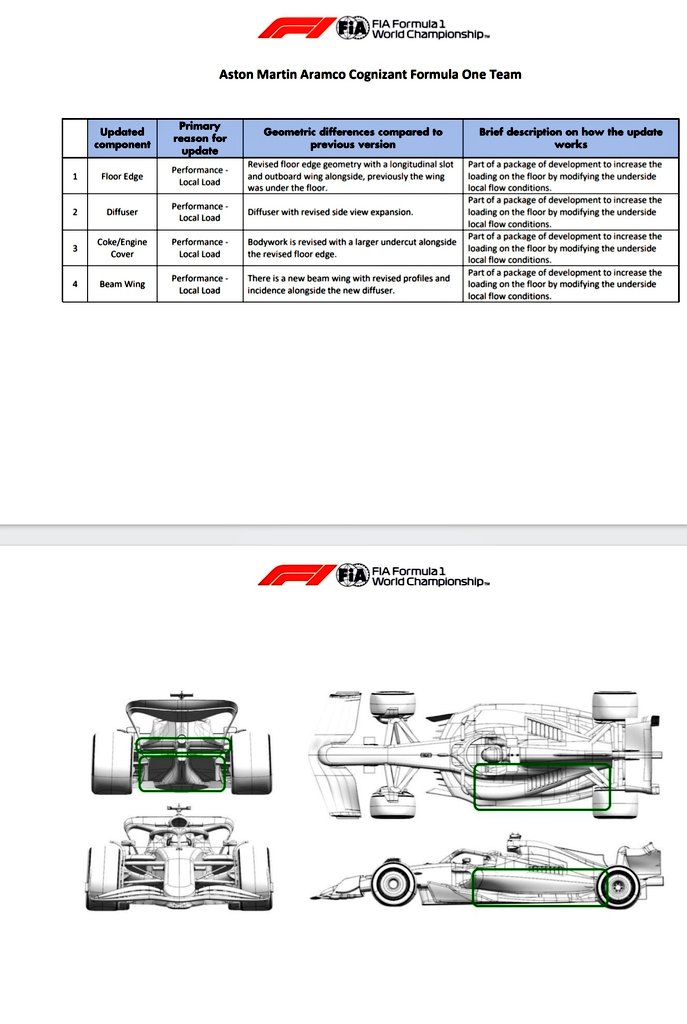

Many were quite surprised when, after one of Lance Stroll's crashes, the floor of his car was exposed, and it was clear that it was very simple, and very poorly worked compared to Red Bull's, which looks like a maze. More than half of the downforce on today's cars comes from that area, and simplicity often doesn't get them very far. So where did this car's initial efficiency come from?

It all points to the front end and its dynamics

It seems that the technicians from Red Bull came up with a series of ideas and indications when it came to attacking the front end of the car. Camber, hardness, angles in excess in the opening of the wheels (the so-called toe in and toe out). All this, in conjunction with a very settled front end, made the AMR23 a typical car to Fernando Alonso's liking: a lot of load at the front, very firm, very reliable and with a more floaty rear end, which he would take care of putting it where it was needed.

[Editor KimiRai's note: He is right that, contrary to popular opinion, it's very important for Fernando to feel the front in order to be competitive. Yes, he can live with some understeer, but it's more complex than that.]

At the beginning of the season they applied all these adjustments, and all of a sudden the car started to run quick, much more than they expected. None of its creators had counted on the records obtained, and in truth they almost couldn't believe it; their forecasts were different.

At Red Bull, the source of the solutions, they have this subject very much in hand, but they work very much in line with their aerodynamic package. The perfect example is their DRS. When Max Verstappen presses the button that operates the servo motor that opens it, he triggers a transformation of his car.

What you see from home is that it opens or closes a wing - a flap, in team terms - but there's more going on. The effect of that flap rhymes with the diffuser, the pylon that holds the rear wing, the exhaust... and at the same time with the position of the front wing, its height, and the way it attacks the air. Two cars coexist inside the RB19: the one that exists with the DRS closed, and the one that is set up when its drivers activate it and it remains open. The key is that for it to work properly, the height of the front wing is critical, and this is what has made the Ferrari work.

Ferrari introduced a new front wing at the Austrian Grand Prix. The result was positive but not ideal. It took two or three races to get it right because of one tiny but crucial detail: its height. The front appendage was good and in the wind tunnel it probably gave them an excellent result. The dilemma is that on the track they struggled to emulate the virtual results.

At Zandvoort they had a lot of problems, and the set-up stalled, something the engineers call "stalling". It seems that at Monza they got it right, they found an optimal way to use it, which led Carlos Sainz to his fifth pole position, and the following race in Singapore to the only non Red Bull victory of the year.

The mystery is that with the current regulations, and that huge downforce from the underside of the car, it is essential to be able to maintain a constant height with the track. Not only that, but adapting to different roughness, bumps, asphalt and variations from one track to the next.

When the single-seater is not perfectly aligned, the same car-window effect can occur. If you're on a motorway at full legal speed and you open a rear window, the car vibrates, resonates, and generates a BRRR-BRRR-BRRR-BRRR-BRRR-BRRR that adds vibration, noise, and in short an aerodynamic problem.

When Formula 1 cars, which go much faster, that misalignment with the track means that by millimetres, the ground effect works or doesn't work. Needless to say, if it doesn't work, a lot of load points are lost, and the cars are very sensitive to changes. Never before have the single-seaters had such an intense and compromised interrelationship between the performance of the suspension, the ride height, and its effect on the air, because without the former, the latter malfunctions. The management of the 2023 single seaters is very similar in concept to karting. The heights are immovable, but you can touch all the settings that affect the kinematics of the front and rear suspension, and here the AMR23 got it right.

The problem for Aston Martin - and this is mere theory - is that the heights, camber and dynamic performance of the chassis is right for the Red Bull it was developed for, but not for the aerodynamics done one floor above. As they have changed parts, and added improvements, they have been elements that instead of helping to achieve this effect, seem to have spoilt it. The hypersensitivity to changes in the current architecture can send to hell everything that millions of euros have been spent on developing.

Aston Martin's engineers are more than correct, they work hard and well, but they have found themselves with a somewhat schizophrenic single-seater, which suffers in its evolution instead of moving towards the light. In front, Mercedes, Ferrari, McLaren or Williams have made progress. These teams seem to have worked on their own designs, concepts and ideas, developed from within; those brought to AM from outside seem to have been bread for today and hunger for tomorrow. They worked for a while, but their efficiency has dissipated as the car has grown in the wrong direction. In the team itself they confess it, and have used the same words.

At Red Bull, apart from Adrian Newey, they have a very polished working dynamic in their chassis-to-aero relationship, and not only do they have their own wind tunnel, but they are just finishing building one across the road from their factory. At Aston Martin they have many hours of use, but they spend Mercedes' during the weekends. What has this got to do with it? Ask McLaren who have had theirs running since this summer, and no longer have to travel to Germany with parts in the technicians' suitcases. They are not doing badly since the change.

Aston Martin is a team under (re)construction. They are very ambitious, they have shown exponential growth, but before titles come victories, before them a good car, and only great teams make good cars. Silverstone are in the process of development, and they have started with the headquarters, which they say many employees are afraid to enter because they get lost inside. It's so big and sophisticated that they have to wander around to find the department they're looking for. This internal joke has happened on occasion, but when they finish putting arrows and directions, and everyone has an assigned chair, everything will start to work in a different, much more effective way. But the car comes later.

In the opinion of several engineers from rival teams consulted, in aero they seem to be stuck somewhere. They think McLaren will be able to catch them and reliability will be key. Sixteen races in, engines and gearboxes are starting to fail, and the teams are certainly planning where they will penalise.

The source of the green ills can come from several places: less optimised improvement processes, fewer people and resources allocated, lower efficiency in the team, and technology that needs to be improved. In the end, we are talking about a growing team that still lacks a bit of everything, and this shows in the development of the car.

That efficiency will, in all likelihood, start in 2024 with a car built by Dan Fallows from scratch, without the weight of a previous concept, born under a new roof, with a different set-up and personnel. That is why this year can be defined as a transition to what Aston Martin will be, and a sign that it will change is that in 2026 it will break away from Mercedes to be powered by Honda. Being a priority customer always gives you an advantage, and that's something you don't currently enjoy being a customer of an engine manufacturer with its own team. In the meantime, let them have it, and as somebody once said, the best is yet to come, but it will take time.