when you dynamically load a part, it goes through cycling. This can be bending a paper clip back and forth or a crank shaft rotating by the force of combustion. if you take a marker and mark a point on the crank journal, you can imagaing that when the point moves from 0 to 180 degrees it goes from tension to compression since it is in a different location but the bearing stresses are applied the same way.

The part will eventually break after a certain number of cycles with a certain amount of force/stress applied to it.

A paper clip bending back and forth will brake in rouhgly 25 bends; try it. It's the alternating of compression and tension that is responsible.

This is called alternating stress, or cyclic stress. The repetitive compressive and tensile loading on a part.

However it is observed that if you reduce the average alternating load you can make the part do more cycles without breaking.

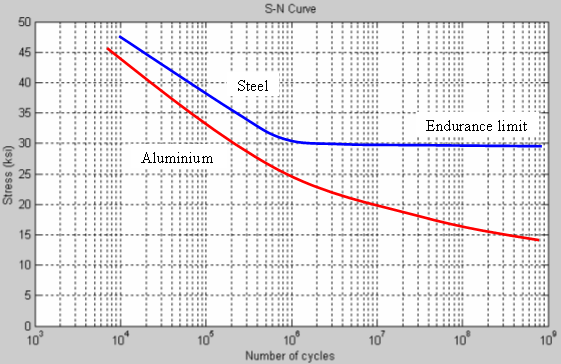

There are materials like steel that if you reduce the stress to a certain point the part can be stressed indefinitely without breaking. This value of stress is called the endurance limit and this occurs when the steel part can do 10 x 10^8 cycles.

or 100 million rotations.

This is shown on the S-N curve abouve, (the stress to cycles curve) and is really the average altenating stress.

For the steel curve you notice that as the stress goes down, the cycles before failure increase, indicating increased life, but there is a point where the cycles continue to increase indefinitely as you stress it (you go across the graph at a value of stress of say 20ksi it doesn't cut the curve) . It is considered to have infinite life; it won't break.

What you notice is that aluminum doesn't have an endurance limit. So no matter how you want to tailor the loads to reduce the stress on the part, it will eventually break at some time after a certain number of cycles (any value of stress will cut the curve at a certain # of cycles).

All aluminum parts will break, and as an example this is why cars with aluminum control arms need those replaced after years of on track abuse. They have stress cracks on them. For steel control arms, the part is more likely stressed within the endurance limit and gives infinite life, so you don't worry about a part failure.

The endurance limit principle is also one of the considerations used to predict how much miles an engine can do as well.

So i think steel pistons is a very wise move in ensuring that you can design them at a certain level and not worry about stress cracks.

On the other hand you can agressively desing a steel part nice small and light and make it fail in 10000 cycles when you know you only want to get 9000 cycles out of it. I think this is what they did in the past with those qualifying engines.