What an exceptionally odd thing to say.autogyro wrote: What, you mean like the law of Moses or Sharia law?

- Login or Register

No account yet? Sign up

What an exceptionally odd thing to say.autogyro wrote: What, you mean like the law of Moses or Sharia law?

Oh dear, you don't "like it", but perhaps you should read up a bit before you call it "bogus"?Per wrote:I don't like Bernouilli's principle. It is a correct observation and it helps 'seeing' (or even, to some degree, calculating) the lift of, for example, an aircraft wing. But many people are misled by the theory because they think that the observation that higher speed corresponds to lower pressure, means that higher speed causes lower pressure. That is bogus.

...

In terms of lift production airflow as a result of Newton's third law actually doesn't provide a large percentage of lift at low Mach numbers. However at transonic speeds (speeds close to the speed of sound) and speeds above the speed of sound this percentage becomes larger.Per wrote:I don't like Bernouilli's principle. It is a correct observation and it helps 'seeing' (or even, to some degree, calculating) the lift of, for example, an aircraft wing. But many people are misled by the theory because they think that the observation that higher speed corresponds to lower pressure, means that higher speed causes lower pressure. That is bogus.

Newton's Laws are a much more sound starting point for understanding aerodynamics. An aircraft wing generates lift because it pushes the air downwards, so it in turn is pushed upwards by the air (3rd Law).

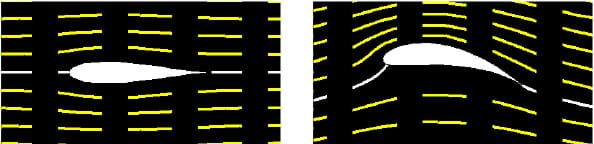

You see, some armchair aerodynamicists use (or rather abuse) Bernouilli's principle and say "the flow over the top of the wing is faster than the flow below the wing, causing lower pressure at the top and hence lift". But they never seem to stop to wonder WHY the air flows faster over the top. The reason is, of course, the lower pressure generated by the object moving through the air. The faster airflow is a side effect of the pressure difference, not the cause of it.

If you read me properly you will see that I do not call the principle bogus, but the conclusion that some people draw from it. The principle relates velocity and pressure, but does not say that the increase of velocity is the cause of the decrease in pressure. However, many people think this is the case.xpensive wrote:Oh dear, you don't "like it", but perhaps you should read up a bit before you call it "bogus"?Per wrote:I don't like Bernouilli's principle. It is a correct observation and it helps 'seeing' (or even, to some degree, calculating) the lift of, for example, an aircraft wing. But many people are misled by the theory because they think that the observation that higher speed corresponds to lower pressure, means that higher speed causes lower pressure. That is bogus.

...

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bernoulli%27s_principle

How would my logic say that both puffs reach the trailing edge at the same time? I don't deny that airspeed over the top surface is faster. So the fact that the puff of smoke over the top will reach the trailing edge faster, seems quite trivial to me (yes the distance over the top surface is longer but that difference is small). Or am I misunderstanding your point?trinidefender wrote:According to your working "knowledge" of the decrease in pressure resulting in an increase in velocity I have this to say to you. There were tests conducted with puffs of smoke in a wind tunnel both over and under a wing. According to your logic, the puffs of smoke would reach the trailing edge of the wing at the same time if the speed increase was purely as a result of an increase in velocity over the top of the wing from a decrease in pressure. However it was found that the puffs of smoke above the wing reached the trailing edge of the wing before the puffs of smoke below the wing. Why exactly this happens is not fully understood. I myself am trying to do more research on it.

I know I was very broad and not very clear in my post it is just these days work has me bogged down and sleeping and studying when I do have time as a result of moving onto a new aircraft type and needing to get my type rating on that aircraft. Company is short on pilots so extra rotations for me as well.thepowerofnone wrote:Per is spot on here, quite how you can be researching this and make a comment like you did trinidefender is beyond me. Whilst normally I have a lot of time for your comments, this one is utterly misleading. Also, congratulations on what sounds like the broadest piece of research I have ever heard of in modern aerodynamics.

Whilst yes, it is true, in the traditional image of Newton's Third Law (momentum down on air = momentum up on wing) real experiments do not show significant enough flow deflection to account for all lift, this is because of viscosity, and vorticity, but make absolutely no mistake that the forces required to make a plane fly or whatever else must be transmitted solely through the air, otherwise physics breaks. I'm sure you know this, but your post wasn't in my opinion clear and could be misleading to the uninformed. It's because of shedding vortices that we don't see this, but if you were to try to bring those vortices to a stop with a wall and a no-slip condition you would experience a force in doing so. Ignoring the real world occurrence of vortex shedding Per is 100% correct, and since vortex shedding is a relatively advanced level of aerodynamics, his explanation was very good.

As he goes on to say, both you and him are actually agreeing about the pressure-velocity relationship: the fact that the puffs don't reach the trailing edge at the same time is precisely why the argument (on a traditional wing) of "flow on upper surface has further to travel in same time; therefore must travel faster; therefore causes low pressure and lift; thus flight" does not work, and that was all Per is on about. Yes if you accelerate a flow, pressure drops, but if you had two different pressures separated by a diaphragm and burst it, the pressure difference would cause an acceleration of flow, therefore the relationship is circular, where many casual observes treat p==f(v), v!=f(p).

I feel like we are all agreeing on the details, just emphasising different areas of the theory. On the matter of your example, absolutely agree, and I have heard another explanation which makes sense to me: if you have a line of cars, all bumper to bumper, travelling at 10 km/h, then as the cars pass some line on the road, they all speed up to 20km/h, the gaps between the cars have to increase to maintain the flow of cars (effectively your mass flow). This affect occurs because the size of the car is not affected by its speed. These gaps effectively represent vacuums in the air, so the mean "gap length:total length" has increased, which if you think about it corresponds to a decline in pressure. All agreed on that front.trinidefender wrote:I know I was very broad and not very clear in my post it is just these days work has me bogged down and sleeping and studying when I do have time as a result of moving onto a new aircraft type and needing to get my type rating on that aircraft. Company is short on pilots so extra rotations for me as well.thepowerofnone wrote:Per is spot on here, quite how you can be researching this and make a comment like you did trinidefender is beyond me. Whilst normally I have a lot of time for your comments, this one is utterly misleading. Also, congratulations on what sounds like the broadest piece of research I have ever heard of in modern aerodynamics.

Whilst yes, it is true, in the traditional image of Newton's Third Law (momentum down on air = momentum up on wing) real experiments do not show significant enough flow deflection to account for all lift, this is because of viscosity, and vorticity, but make absolutely no mistake that the forces required to make a plane fly or whatever else must be transmitted solely through the air, otherwise physics breaks. I'm sure you know this, but your post wasn't in my opinion clear and could be misleading to the uninformed. It's because of shedding vortices that we don't see this, but if you were to try to bring those vortices to a stop with a wall and a no-slip condition you would experience a force in doing so. Ignoring the real world occurrence of vortex shedding Per is 100% correct, and since vortex shedding is a relatively advanced level of aerodynamics, his explanation was very good.

As he goes on to say, both you and him are actually agreeing about the pressure-velocity relationship: the fact that the puffs don't reach the trailing edge at the same time is precisely why the argument (on a traditional wing) of "flow on upper surface has further to travel in same time; therefore must travel faster; therefore causes low pressure and lift; thus flight" does not work, and that was all Per is on about. Yes if you accelerate a flow, pressure drops, but if you had two different pressures separated by a diaphragm and burst it, the pressure difference would cause an acceleration of flow, therefore the relationship is circular, where many casual observes treat p==f(v), v!=f(p).

Let me see if I can dig up some NASA articles and whatever else I have saved and get back to you with a more detailed and thorough approach to the whole question of lift being attributed to Bernoulli's theory and newtons laws relating speed to the whole thing.

Well food for thought. You take a piece of paper. Hold it at one end horizontally to your mouth. You will notice that the piece of paper hangs down progressively more the further away from where you are holding it. Blow along the top of the flat side of the paper and watch the piece of paper lift up. To me this would appear as the increase in velocity of you blowing air over the top of the piece of paper is associated with a reduction in pressure and henceforth lift on the piece of paper being created.

I think this is an over complication, the wings are shaped they way the are for a reason. The air flows faster over the top simply because of the shape of the wing and its not a side effect of the pressure difference but rather the cause of the pressure difference. That the faster airflow causes a pressure drop (or differential) is easily demonstrated by observing a fluid flow through a diffuser (or via dynamic pressure eqn (1/2 ρv^2)).But they never seem to stop to wonder WHY the air flows faster over the top. The reason is, of course, the lower pressure generated by the object moving through the air. The faster airflow is a side effect of the pressure difference, not the cause of it.

I will ask you one question in response: what is the condition for a particle of air to accelerate? (note - "simply because of the shape of the wing" is not considered a correct answer)mcdenife wrote:Per Wrote:I think this is an over complication, the wings are shaped they way the are for a reason. The air flows faster over the top simply because of the shape of the wing and its not a side effect of the pressure difference but rather the cause of the pressure difference. That the faster airflow causes a pressure drop (or differential) is easily demonstrated by observing a fluid flow through a diffuser (or via dynamic pressure eqn (1/2 ρv^2)).But they never seem to stop to wonder WHY the air flows faster over the top. The reason is, of course, the lower pressure generated by the object moving through the air. The faster airflow is a side effect of the pressure difference, not the cause of it.