well...where to start...?

RIDE HEIGHT:

The very general statement is that the closer your diffuser is to the groud, the more downforce it produces (exponentially), until stall happens.

In this link you'll find two images showing the most interesting condition to analyze, transition from a steady to a turbulent flow, with consequent stall of a diffuser:

http://www.vx220.org.uk/forums/topic/12 ... nd-design/

That's just a basic simulation, but we can observe how the "boundary layer/total flow" ratio increases as the floor gets nearer to the ground (meaning less energized flow). This condition promotes separation between the main stream and the diffuser, with a consequent loss of extraction capabilities from the diffuser itself.

Great article with simulations and graphs you were asking for (from Keith Young):

http://consultkeithyoung.com/content/cf ... ide-height

In more complex systems (F1 aerodynamics...), controlled vortices are used to re-energize the flow, delaying the separation.

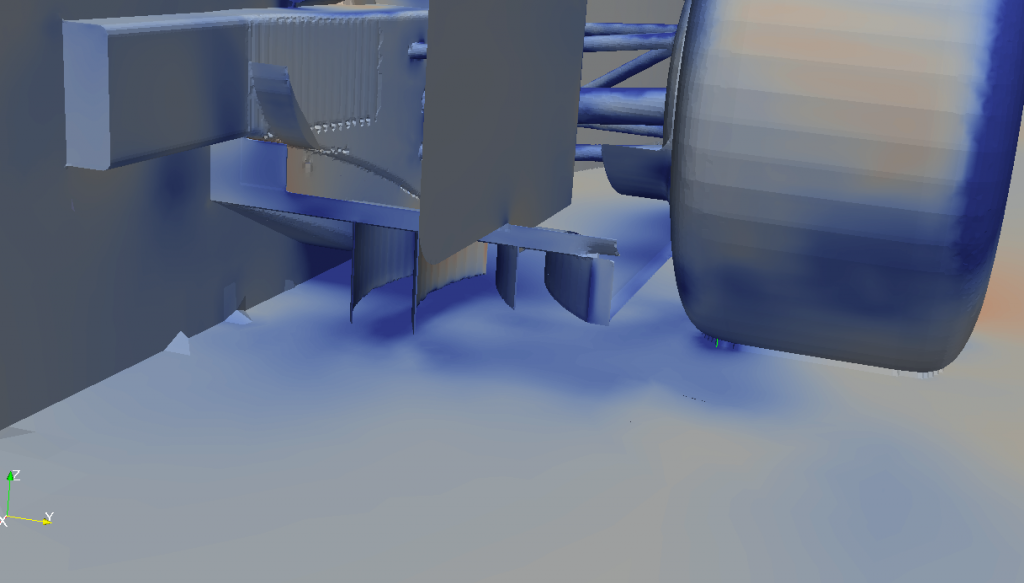

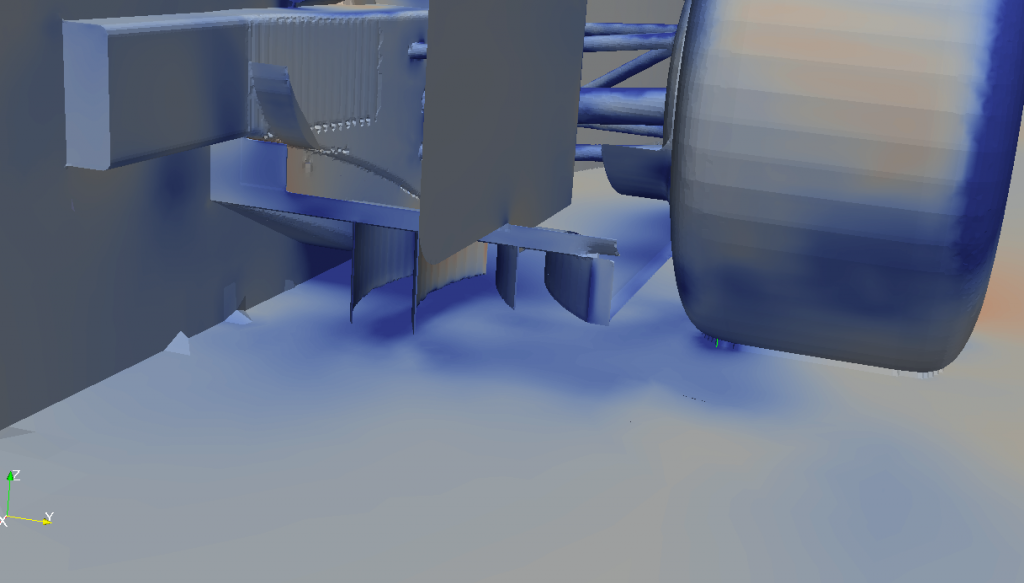

However vortices are also affected by ride height, as we can see here:

Another consideration: in real life ride height, pitch condition and flow quality do change very often and very quickly, forcing the diffuser to work in worse conditions, where stall is much more likely to happen and reattachment of the flow much harder.

PITCH ANGLE:

I think this other article from Keith Young needs no further words:

http://consultkeithyoung.com/content/cf ... user-angle

DIFFUSER SHAPE:

(the following comes from my personal experience with CFD)

Diffuser's aim is to accelerate and extract the greatest amount of air from the floor in order to produce downforce. However the diffuser itself produces a considerable amount of downforce on its own as it is a low pressure paradise. Therefore the main target is to find the best compromise between a diffuser that works better at extracting air from the floor but produces less downforce on its own, and a diffuser that does the opposite.

_Convex diffusers have a lower expansion ratio (meaning they are "gentler" at extracting air), but are less susceptible to stall; also, given their shape, they produce more downforce on their own compared to concave diffusers (these are the reasons why we don't find concave shapes on ordinary wings).

_Concave diffusers have a higher expansion ratio but less capability of producing downforce on their own. However, since they interact with the mandatory flat floor typical of F1 cars, they do produce more downforce overall. That happens because its shape properties (or, in other words, its greater expansion ratio) focus the low pressure area on its throat (the area between the floor and the diffuser itself), allowing for a greater interaction and better extraction between the diffuser and the floor.

_Hybrid diffusers (concave and then convex) are the compromise i was talking about.

Now some numbers:

i've designed and tested with decent accuracy different kinds of diffusers. They were tested with an actual F1 model around.

Model with Convex diffuser without strakes: 780N on the rear axle. (drag: 914N)

Model with Hybrid diffuser without strakes: 800N on the rear axle. (drag: 903N)

Model with Convex diffuser with strakes: 895N on the rear axle. (drag: 918N)

Model with Hybrid diffuser with strakes: 920N on the rear axle. (drag 908N)

I'd like to underline that every design was optimised to actual car's necessities in order to produce downforce.